Cranial Cruciate Ligament injuries in Dogs

The cranial cruciate ligament (CCL), also known as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), is the main stabiliser of the stifle joint (knee). CCL tears are the most common orthopaedic problem in dogs, & typically occur secondary to degenerative changes in the ligament; in extreme cases, dogs may be affected as early as 3 or 4 months of age. A number of factors may influence the early onset of degeneration including genetics, sex, hormones & obesity, & degenerative changes will typically affect the CCL in both stifles. Purely traumatic injuries are rare, although trauma may be associated with tearing of an already weakened ligament.

Treatment Options: TPLO, TTA , ECR & TTO

There are a number of surgical techniques that can be used to manage a tear of the CCL, & your vet may have discussed various options with you. The most commonly performed procedures are tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO), tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA), various lateral extracapsular suture techniques (ECR), and to a lesser extent, triple tibial osteotomy (TTO). TPLO is currently considered the gold standard for the management of cranial cruciate ligament injuries in dogs and is the procedure most commonly favoured by orthopaedic surgeons.

TPLO (Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy)

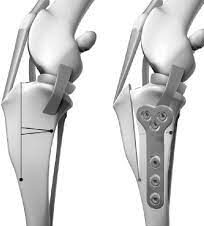

TPLO involves making a curved cut (osteotomy) in the top of the tibia (shin bone), rotating the separated segment of bone (the tibial plateau) & securing it in a new position with a bone plate & screws. This results in an immediate & permanent alteration to the biomechanics of the knee, dramatically reducing cranial tibial thrust thus creating dynamic craniocaudal stability; TPLO achieves a biomechanical advantage by permanently altering the angle between the patella tendon & tibial plateau. In simple terms, the knee no longer needs an intact cranial cruciate ligament to be stable. Prior to cutting the tibia the joint is inspected, the menisci (joint cartilages) examined & any damaged meniscal tissue removed. Any remnants of the cranial cruciate ligament are usually completely removed; however, if the majority of the ligament is intact & functional the torn fibres may be debrided & the remaining ligament left in place. X-rays are taken at the completion of surgery. X-rays are typically repeated approximately six weeks after surgery to assess bone healing & implants.

TPLO is widely considered the most reliable and predictable surgery for cranial cruciate ligament disease currently available. This is supported by a growing number of publications in the veterinary literature which present objective evidence of superior results for TPLO versus both TTA and ECR (click the following link for a summary of the published evidence with references). TPLO vs TTA vs ECR vs TTO as surgical options for cranial cruciate ligament tears

TTA (Tibial Tuberosity Advancement)

TTA involves making a straight cut at the front and top of the tibia (shin bone), effectively cutting off the tibial tuberosity, where the patella tendon attaches. The tuberosity is then moved forward (advanced) and secured in position. The original technique used a titanium cage as a spacer, in addition to a titanium bone plate, forks, and screws. Numerous variations of the original procedure have been described: these include using a titanium foam wedge instead of a cage (MMP) or using an extended cage that is fixed in position with multiple screws and not using a plate (TTA Rapid). Tibial tuberosity advancement results in an immediate and permanent alteration to the biomechanics of the knee, reducing cranial tibial thrust, thus improving dynamic craniocaudal stability; in simple terms, the knee becomes more stable. Prior to cutting the tibia the joint is inspected, the menisci (joint cartilages) examined and any damaged meniscal tissue removed. Any remnants of the cranial cruciate ligament are usually completely removed. X-rays are taken at the completion of surgery. X-rays are repeated approximately six weeks after surgery to assess bone healing and implants. Further x-rays may be scheduled approximately three months following surgery to check the bone has completely healed.

ECR (Extra-Capsular Repairs e.g. lateral suture)

The traditional technique of extracapsular repair (ECR) places the “origin” of the suture (typically nylon) around a small bone and ligament (fabella) at the back of the stifle. The suture then passes through a bone tunnel in the tibial tuberosity. Early stretching and/or breaking of the suture is problematic; contributing factors include the material used and the location of the fixation points. The isometric ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene lateral suture (IPLS) aims to address some of these shortcomings. Ultra-high molecular weight spun polyethylene is used in place of nylon; it is substantially stronger and less prone to stretching. The placement of bone tunnels in the femur and tibia at specific locations allows more secure fixation and quasi-isometric placement of the suture. An isometrically placed suture remains at relatively constant tension through a full range of motion of the stifle; a suture placed in a non-isometric position (as per traditional technique) will become excessively lax or tight depending on the position of the knee, resulting in both instability and reduced range of motion of the stifle. Prior to placing the IPLS the stifle joint is inspected, the menisci (joint cartilages) examined and any damaged meniscal tissue removed. Any remnants of the cranial cruciate ligament are also removed.

TTO (Triple Tibial Osteotomy)

The TTO involves making three cuts at the top of the tibia (shin bone). It combines aspects of both tibial tuberosity advancement and wedge osteotomy.

There is no published data comparing triple tibial osteotomy (TTO) to any other technique used in the management of canine cruciate ligament insufficiency. i.e. there is no scientific evidence that performing TTO yields results that are any better, or even as good as placing a lateral nylon suture (ECR), let alone extensively studied osteotomy techniques such as TPLO. In the absence of supportive data and given the potential for serious complications as reported in the veterinary literature it is difficult to justify recommending TTO ahead of other widely studied and proven alternatives.